I'll tell you right up front, it's going to entail a lot of hard work.

And it will take time. Not to be coy or anything, but this is inevitably going to be a ridiculously extended series of posts. You gotta start somewhere though, right?

This side of the big island is rife with wonderful old houses that have seen better days. Since even before we moved here, it's been my dream to somehow get one of these tumbledown old shacks, dismantle it down to its roots, and salvage all of the materials that I can.

See, many of these old houses were made from some nice materials, stuff that is virtually unobtainable today, at least not without selling your child into slavery. Renee says that option is off the table however, so it looks like a-scavenging I will go.

A wonderful woman who bought a piece of property a few years back (just outside of Pahoa) had exactly that sort of place, the tumbledown shack. The house was too far gone to be salvaged, so they tore it down, saving and reusing what they could. New construction in Hawaii does not allow for the use of used or salvage materials, but at least they could use some of the old siding lumber to build a fence. They also saved the windows, and that's where I come in.

This is stack of old sash windows, at least 3/4 of which I should be able to make good again. For some inspirational reading, I refer back to a Shinglemaker post a while back, on rejuvenating some of his old Dutch beauties. These windows won't be too terribly different and I'll go into the details of the restoration agonies in a future post.

I am pretty excited to begin with the fixing, because it will be a crash course (no pun intended) in how things used to be done. Many of these windows were built the old way, by hand, lots of through tenon, wavy glass, and unfortunately, some termite damage. I'm also looking forward to using the old-school lime/linseed oil putty, something that I've never made or used before, but who's qualities I've heard worshipfull references to for ages.

So I got all of the old windows, and while I was there, I cleaned up the site a bit, picking up the leftovers that were headed for the burn pile.

It took a few trips with my little car, but I've got most of it home now. That's a big pile of old growth redwood siding, totally clear (no knot holes), something that I can't even imagine trying to buy now, just WAY too expensive. Expensive to buy new, but every day tons of this stuff is tossed into the dumpsters island wide. I had been looking for exactly this type of material, to use for building my traditional Japanese forge bellows, the fuigo. Tight CVG redwood was tops on my list of materials to use and.........here it is. Now I just need to pull a bazillion nails and scrape off the old paint.

Also while I was there, the owner brought in a crew to cut down some of the larger nuisance trees that were in the immediate area. Most notably were four smallish Albizia, generally referred to as "That G#*!!!!#%#%*{+}!!!!), and any number of less polite epithets, dependant upon present company. Smallish in size, all four are only about 24" in diameter, which ages them at about 10-15 years old or so. The owners decision to remove them now is a sound one because these trees grow incredibly fast, and though the trees themselves are beautiful, they are also weak and prone to shedding monstrous limbs at the slightest provocation. They call this the "Albizia tree epidemic", and it is a legal liability nightmare.

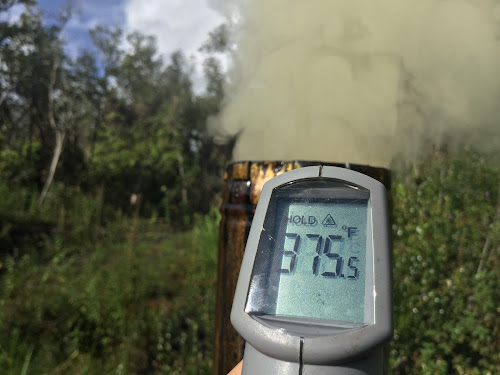

The owner had girdled this tree last year, so it has been seasoning for that time, loosing some of its moisture and all of its leaves.

I asked the tree crew to leave me a good sized section of the main trunk, so that I can try my hand at working with this stuff, cutting planks mostly. The Albizia wood isn't commonly used, and is generally considered to be trash, barely worth even chipping for mulch. People don't even use it for firewood. That sounds about perfect for me, with my penchant for trying to find a better use for everyone else's garbage.

The crew left me four trees, about 50' linear feet of 2' diameter logs. That's about the same volume of area as what my car occupies. My arms are feeling bigger already!

And.

That's just the main stems. There are huge amounts of limbs still laying everywhere. It's funny to me, seeing a 1' diameter limb, 10' long and thinking....ehh, what's the point of cutting that little crap?! And these trees aren't even particularly large. Some of these monsters are closer to 5' diameter.

Like a fool, I forgot my inkline to mark the initial cut, so I had to eyeball it and was wandering all over the place. Not pretty.

Pardon the forced perspective, they aren't really as big as they appear. Even after splitting the 12' log, I still had to shorten the lengths to 6' so that I could move them around, much less squeeze them into my poor little car.

Once I got home, I slapped some paint on the endgrain to slow the drying some, try to minimize the checking. I still need to strip the bark, if I hope to save the wood from the beetle larvae.

Sammy likes them.

Opening these logs up was like seeing an old friend. I realized that this is most likely the same type of wood that gets used as a lightweight core stock on some of the solid core plywood panels that I've bought in the past. The panel manufacturer rips the core into strips, glues them back together, and finally, glues down an attractive face veneer.

This log shows rather bland grain, but nothing objectionable. The color is a light tan and cream thankfully, as some of the other stuff that I've seen has a distinct greenish cast to it, green with undertones of mud.....yuck. The fuzzyness that is apparent in places seems to indicate that the grain will be slightly interlocked but again, nothing surprising.

My immediate impression of the wood is that it will make for some interesting furniture building, if not the house. The wood is light in weight and considered brittle. It's not rot or insect resistant either, so if we were to use it for building, it would be interior only. I look at the wood and see.....thick tabletop surfaces, or very thin panel stock. I think that this wood has good potential, and it's free for the asking. You could get a mountain of this stuff in days, if you had a loading truck and trailer. I've read technical papers that measured it's overall strength to be somewhat on par with eastern White Pine, which is what got me interested in this lumber in the first place. Let's find a use for this stuff.

One of the many other nuisance trees that were cut, were a handful of Cecropia. I used some of the shorter pieces as sleepers to keep the Albizia off the ground.

Growth rings! I haven't seen that in a while.

The center pith is hollow with very thin and brittle membranes that divide the length. One of the common names of this plant is "Pump-wood", and it's obvious why. It would be an easy task to push a stick through the divisions, creating a long, hollow tube. That would make for some very rustic plumbing, but sanitation might be questionable.

It has distinctively radiant, palmate leaves.

The leaves look a bit similar to the Jamaican castor bean plant, and nearly everyone that I've met has the mistaken impression that it IS the castor bean, but it's not. If you were hoping to make some Ricin, you're SOL......sorry.

Back to Cecropia obtusifolia .....

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/

There is some very interesting reading there. Turns out its got a muriad of tradition and modern medical uses, a far more interesting character than just being on the "100 worst invasive plant species" would indicate. In retrospect, it seems like it's often the most prolific and resilient species that have the potential for having interesting qualities. I've always had a sympathy for difficult personalities.

The general consensus is that it is a weak and non-durable wood, opportunistic in disturbed areas and it has large, stinky blossoms too. From my limited experience, it feels pretty strong to me, so I'm looking forward to exploring it's potentials in the near future.

So what has this to do with building cheaply? I guess that it's obvious, but I'm finding that free materials abounds, if you've got the knowledge and energy to invest in the gathering.

Oh yeah.....time. This is a huge time element here. You can't just start building tomorrow, you know?