So I built this charcoal kiln to make proper bladesmithing charcoal.....If you want to see it from the beginning:

It's ugly, I'll grant you that, haha.

How did yesterday's burn work out?

Not the greatest I've made....

.....but not the worst, either. It looks badly overcooked. The barrel is only half full, but started out being packed.

Given that this was a newly constructed kiln, surrounded by wet grass/clay insulation (didn't work, BTW), and filled to the brim with wood that was far from dry....my expectations were low. I was anticipating a lot of undercooked stuff though, so go figure. This was probably a worst case scenario, so the results are encouraging.

My only real successes in the past have been using a 5 gallon retort style kiln. I've cooked in 55 gallon drums a few times before, but that only resulted in badly overcooked or badly undercooked charcoal. Certainly nothing approaching a consistent result, anyways. What did I get this time?

The first shovels don't look so hot (no pun intended). This ashy, shrunken and fractured look is overcooked. Too much heat, over too long a time period.

I sift out the fines using a nominal 1/2" mesh.

When I first opened the barrel, it looked to me as though much of the wood had been reduced to ashes –generally that's due to having an air leak somewhere– but as I am sifting, I'm not really finding as much ash as I had thought.

I do find a couple of pieces that aren't fully cooked. This chunk is 1/2 charcoal, the other 1/2 still a little bit brown.

You can still see the holes in the wood, tunnels left by beetle larvae. So cool!

Here is a perfect example of overcooked charcoal. Spongy looking, soft rounded edges, and a gray cast to it.

This is charcoal that has had all of the volatile elements burned from it, not really what we want for the forge. It's great for the garden though. I am surprised how little there is of this. Only 4-5% of the total, if that. I got similar results when using my 5 gallon retort.

Most of the charcoal came out looking like this. A perfect piece is on top, a slightly overcooked piece below.

The perfect charcoal breaks cleanly with a crisp *snap*. You can see how fine grain this Guava is. That is another variable to this attempt, I've never cooked a hardwood species, much less Guava. I've only used softwoods in the past.

A before and after comparison.

One of the aspects that I love the most is how little the wood is affected by a proper coaling process. If done well, the charcoal product will look exactly like the original, just shrunken and black after having all of the liquid components removed. The Japanese have turned this into an art of sorts, converting all sorts of things into charcoal themed displays.

I recognize a pineapple and a sea urchin, but the other stuff? Is that a lufa sponge?

My guava charcoal isn't that pretty, but you can see how many of the sticks had fissured, peeling bark when they went into the kiln and still have it upon coming out.

You can see evidence of the larvae tunneling underneath the bark. I just love this stuff.

It's hard to tell from the photos, but the charcoal itself has a silvery sheen to it, and it rings slightly when tapped. Pouring the charcoal into the bag, it has a musical sound to it.

And here is the yield. A small 4 lb bag of fines (mostly the small fragments of bark that fell off of the sticks), and a large bag of decent charcoal.

This Guava charcoal is MUCH heavier than the pine and cedar charcoal that I am used to. I would guess that the bag weighs around 70lbs, more than the bag can withstand in any event, so somewhere around there.

The small bag of fines can be crushed further and used for the bed of my forge, added to the clay for yaki-ire, used as a component of the welding flux, or just spread in the garden. Nothing is wasted.

Here is the barrel after shoveling out the interior. I took no special care here, just scooped out the charcoal, but my point is that there was actually very little ash produced, far less than I was expecting.

So in retrospect, the yield wasn't as poor as I had initially thought. The cooked charcoal is dramatically reduced in diameter after losing all its water, and also had settled quite a bit. It's hard for me to guess at a yield, but based primarily on the amount of ash I saw.....jeez, 80% maybe?

Another good thing about proper charcoal.....it's clean. Well, kinda clean.

Despite having shoveled out a whole drum of char, screening it all and bagging it, my hands are barely dirty. My feet are still clean! It's nice stuff.

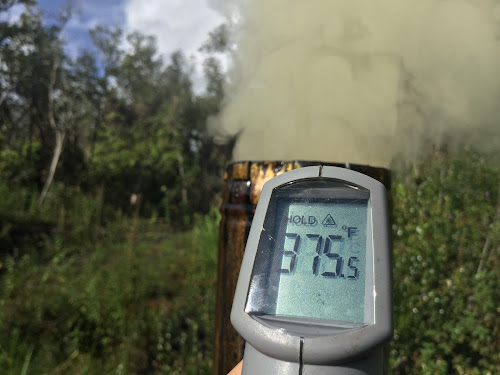

This particular batch of charcoal doesn't have the clear pure *ring* of some charcoal, but had I started with dry sticks to begin with, I suspect it would. The next batch (I'll probably start today....I'm a charcoal junky, haha) I will shut down sooner, earlier in the blue smoke phase, so we'll see how that affects things. The kiln is dry now too, not buried in wet mud. That should help. This charcoal will be fine to use, but I still want to do better.

Another improvement will be to construct the fire chamber to be more like a self feeding rocket stove, with a tilted or vertical entry for the fuel sticks. Put gravity to work for you, right? Nothing too fancy though, because you need to be able to seal the coaling chamber quickly.

So, a success! If you are into traditional blacksmithing and need some fuel, this works well. We've got tons of downed trees sitting here that I need to clean up, nearly all of it being thin, invasive guava that everyone else hates. I haven't used the guava charcoal in the forge yet (still haven't built my forge even, so I guess that I better hurry up, huh?), but this should work fine. There is a never ending supply of free guava here.

This is a great way to use what many people view as waste, and that's a huge positive in my book. Cut the tree, and what isn't suitable for lumber gets turned into charcoal. The smallest twigs and twistiest branches are used to actually make the charcoal, while the leaves go into the garden compost.

The only real problem that remains is the noxious smoke thing. Maybe we can devise a scrubber for the vent stack. One of the more common uses for the Iwasaki kiln is to capture the "Wood vinegar" distillate, used for lots of different things but I'm not really familiar with that side of stuff. Essentially, the smoke gets funneled into a long cooling pipe, then condenses back into a liquid which then is collected. Something to think about. It might be worth a shot.

My charcoal producing kiln is not really an original idea (nothing is, right?), but is loosely based on a traditional Japanese coaling kiln.

http://blogs.yahoo.co.jp/okakawa2/62354573.html

The fire never actually touches the wood that will be turned into charcoal, and the blue line presumably represents the liquid distillate. The traditional kiln is packed with wood as tightly as possible, but much of the wood is stacked vertically, and there doesn't appear to be an air channel underneath the wood, only a small space that runs just under the ceiling. I might try this next firing.

The 55 gallon drum that the design is based around has a limited service life, so perhaps I will make the real version one day. That a fun class that would be!

So there you have it. Now you can make awesome charcoal too. It's pretty easy and might even be called fun. If the neighbors get fussy, have them come talk to me.

Now if only I had a forge......